China just fought back in the semiconductor exports war. Here’s what you need to know. – MIT Technology Review

The country aims to restrict the supply of gallium and germanium, two materials used in computer chips and other products. But experts say it won’t have the desired impact.

MIT Technology Review Explains: Let our writers untangle the complex, messy world of technology to help you understand what’s coming next. You can read more here.

China has been on the receiving end of semiconductor export restrictions for years. Now, it is striking back with the same tactic. On July 3, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce announced that the export of gallium and germanium, two elements used in producing chips, solar panels, and fiber optics, will soon be subject to a license system for national security reasons. That means exports of the materials will need to be approved by the government, and Western companies that rely on them could have a hard time securing a consistent supply from China.

The move follows years of restrictions by the US and Western allies on exports of cutting-edge technologies like high-performing chips, lithography machines, and even chip design software. The policies have created a bottleneck for China’s tech growth, especially for a few major companies like Huawei.

China’s announcement is a clear signal it aims to retaliate, says Kevin Klyman, a technology researcher on the Avoiding Great Power War Project at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. “Every day the technology war is getting worse,” Klyman says. “This is a notable day that accelerated things further.”

But even though they immediately sent the price of gallium and germanium up, China’s new curbs are not likely to hit the US as hard as American export restrictions have hit China. These two raw materials, though they are important, still have relatively niche applications in the semiconductor industry. And while China dominates gallium and germanium production, other countries could ramp up their own production and export enough to substitute for the supply from China.

Here’s a quick look at where things stand and what comes next.

Gallium and germanium are two chemical elements that are commonly extracted along with more familiar minerals. Gallium is usually produced in the process of mining zinc and alumina, while germanium is acquired during zinc mining or separated from brown coal.

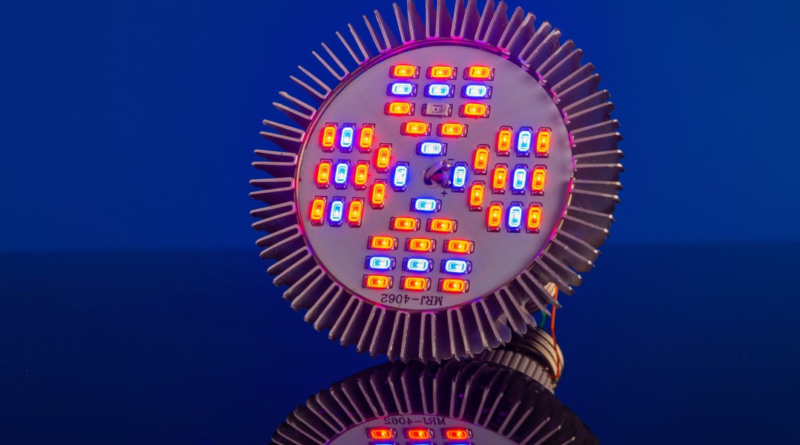

“Beijing likely chose gallium and germanium because both are important for semiconductor manufacturing,” says Felix Chang, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. “That is especially true for germanium, which is prized for its high electrical conductivity. Meanwhile, gallium has unusual crystallization properties that lead to some useful alloying effects.” Gallium is used in the manufacture of radio communication equipment and LED displays, while germanium is widely used in fiber optics, infrared optics, and solar cells. These applications also make them useful components in modern weapons.

Currently, about 60% of the world’s germanium and 90% of the world’s gallium is produced in China, according to the Chinese metal industry research firm Antaike. But because China doesn’t have the capacity to turn these materials into later-stage semiconductor or optical products, a big chunk of it is exported to companies in Japan and Europe.

The new export license regime will start being implemented on August 1. Right after it was announced, purchase orders reportedly began swarming into Chinese gallium and germanium producers. The stockpiling has raised the price of the two materials, as well as the stock prices of Chinese companies that produce them.

AXT, an American maker of semiconductor wafers, quickly responded to say that its China-based subsidiary would apply for an export license to maintain business as usual.

It’s important to remember that this is not a ban but a licensing system, which means the impact will depend on how difficult it is to secure an export license. “We see no evidence that no licenses will be granted. They will not be granted to US defense contractors, I imagine,” says Klyman, who notes that American defense companies Raytheon and Lockheed Martin were the first two names added to China’s newly established “unreliable entity list” earlier this year.

But the ability to control who can be granted the permits will give China more leverage in trade negotiations with other countries, particularly those—like Japan and Korea—that rely on such imports for their own semiconductor industries.

The US government has spent the past year lobbying allies to join forces in restricting China from sourcing high-end chipmaking equipment like lithography machines, and the results are showing. In June, both Japan and the Netherlands announced their decisions to restrict the export of chip-related materials and equipment to China. China certainly is feeling the pressure, and its attempts to negotiate with the US on the restrictions have been unsuccessful.

Aggressive new US policies will be put to the test in 2023. They could ultimately fragment the global semiconductor industry.

Many experts point to the China visit of Janet Yellen, the US secretary of the treasury, which happened last week, as the major reason these export controls were announced when they were. “Beijing was … sending a signal before the Yellen visit that China will play the game of controlling exports in key sectors of concern to the US government,” says Paul Triolo, a senior vice president for China and technology policy lead at the consultancy Albright Stonebridge Group. Control of gallium and germanium is one of the tools Beijing wields to push the US and its allies back to the negotiation table.

There’s also a strategic concern that holding onto these critical materials could serve China’s interests if a conflict breaks out, says Xiaomeng Lu, director of geotechnology practice at the Eurasia Group. “Russia has been pretty much blocked out of the global tech ecosystem at this point … but they still have oil, they still have food, and that’s how they survived. That’s the worst-case scenario Chinese leadership keep at the back of their mind,” Lu says. “If the worst-case scenario happens, we need to hold the raw materials that we have in our reserve as much as possible.”

The Chinese government may be seizing stronger control of the supply chain for now, but the added uncertainty of the licensing regime will cause foreign importers of gallium and germanium to look elsewhere for a more reliable supply. Most people agree that these export restrictions may not be beneficial to China in the long run.

“My read is that the US government is happy about this move,” says Klyman. “This forces suppliers to diversify their supply of gallium, germanium, and other critical minerals, and it will cause markets to reinterpret the value of mining in North America and other regions.”

Mining companies in Congo and Russia have already said they intend to increase production of germanium to meet demand. Some Western countries, including the US, Canada, Germany, and Japan, also produce these materials, but ramping up production could be difficult. The mining process causes significant pollution, which was one of the reasons production was offshored to China in the beginning.

“The West will have to accelerate its innovation of new processes to separate and purify rare-earth metals. Otherwise, it may have to relax the environmental regulations that constrain traditional separation and purification techniques in the West,” says Chang.

Probably not. Germanium and gallium can be mined elsewhere. But cutting-edge technologies are more restricted in their availability; the EUV lithography machines that the US wanted barred from export to China, for example, are made by a single company. “Export control is not as effective if the technologies are available in other markets,” says Sarah Bauerle Danzman, an associate professor of international studies at Indiana University Bloomington.

The US also has other advantages that make export control work more efficiently, she says, like the international importance of the dollar. The US chip curbs have an extraterritorial effect because companies fear being sanctioned if they don’t comply. They could be excluded from receiving payments in US dollars.

For China, the export controls could hurt its own economy, Bauerle Danzman adds, because it relies more on export trade than that of the US. Restricting Chinese companies from working with the rest of the world will undermine their business. “Unless [China] is going to get Japan and South Korea and the EU to agree to not trade with the US, in order for it to really execute on a strategy like this, it not only has to stop exports to the US—it has to stop exports to basically everywhere,” she says.

This is not the first time China has tried to restrict the export of raw materials. In 2010, it reduced the allotment of rare-earth elements available for export by 40%, citing an interest in environmental conservation. The same year, the country was accused of unofficially banning rare-earth exports to Japan over a territorial dispute.

Rare-earth elements are used in manufacturing a variety of products, including magnets, motors, batteries, and LED lights. The quota was later challenged by the US, EU, and Japan in a World Trade Organization dispute. China’s environmental protection justifications didn’t convince the settlement panel. It ruled against China and asked it to roll back the restrictions, which happened in 2015.

This time, the Japanese government has again said it could raise the issue with WTO, but China likely won’t need to worry about it as much as the last time. With the rise in trade protectionism and self-preserving supply-chain policies during the pandemic era, the organization has increasingly lost its authority among member countries. “Today, WTO is less relevant, and China is trying to find a more nuanced policy argument to back up their actions.” says Lu.

It doesn’t need to look far. In December, China filed a dispute with the WTO around the US semiconductor export controls, calling them “politically motivated and disguised restrictions on trade.” In a brief official response, the US delegate to the WTO said every country has the authority to take measures it considers “necessary to the protection of its essential security interests,” an argument that China can easily use for itself.

China most likely won’t stop at gallium and germanium when it comes to export controls. Wei Jianguo, a former Chinese vice minister of commerce, was quoted in the state-owned publication China Daily as saying that “this is just the beginning of China’s countermeasures, and China’s toolbox has many more types of measures available.”

Gallium and germanium, while important, don’t represent the worst pain China could inflict on the raw materials front. “It’s giving the global system a little pinch, showing that we have the capability to cause a bigger pain sometime down the road,” says Lu.

That could come if China chooses to clamp down again on the export of rare-earth elements. Or the materials used in making electric-vehicle batteries—lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite. Because these materials are used in much greater quantities, it’s more difficult to find a substitute supply in a short time. They are the real trump card China may hold at the future negotiation table.

Tariffs and IRA tax incentives are starting to reshape global supply chains—but vast challenges lie ahead, explains Shawn Qu, founder of Canadian Solar.

The rapid pace of AI has put more emphasis on individual contributors at the executive level. Capital One's Grant Gillary explores the unique challenges of being a senior engineering executive and an individual contributor.

How Big Tech, startups, AI devices, and trade wars will transform the way chips are made and the technologies they power.

Emily Baker hopes her designs can make it cheaper and easier to build stuff in disaster zones or outer space.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

© 2024 MIT Technology Review