Applied Materials, Lam Research and KLA could be hurt by new trade restrictions on China — even though those rules … – Silicon Valley Business Journal

Listen to this article 3 min

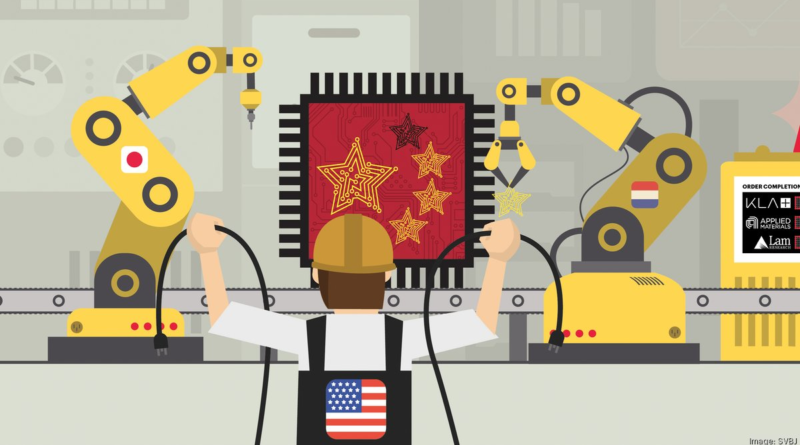

The Biden administration is aiming at China's access to tools from ASML and Nikon. Silicon Valley's semiconductor equipment makers could be caught in the crossfire.

Three local companies that play a crucial role in the chip industry could be caught in the crossfire amid an effort by the Biden administration to restrict Chinese access to advanced technology.

Silicon Valley is well known for being home to chip makers and designers like Intel Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc.; such companies gave the region its name, after all. But it’s also home to less prominent businesses that play just as important a role, because they make the ingenious and often expensive tools that actually manufacture semiconductors.

Three of the largest companies in that industry are Applied Materials Inc. in Santa Clara, KLA Corp. in Milpitas and Lam Research Corp. in Fremont. Those corporations sell to chip makers like Intel, which has installed their equipment in its factories in Oregon, Arizona and will eventually do so in Ohio. Collectively, those three companies account for 40% of what’s expected to be an $80 billion market for semiconductor equipment.

But these Silicon Valley tool makers are at risk from a deal that on the face of it has nothing to do with them. The Biden administration recently struck an agreement with the Netherlands and Japan to restrict companies in those countries from exporting specific versions of their own chipmaking equipment to Chinese manufacturers, according to sources and reports.

Without the equipment sold by the Dutch ASML Holding N.V. and Japanese Nikon Corp. the Chinese chipmakers would have no use for some of the Silicon Valley equipment manufacturers’ tools. Because ASML and Nikon are the only companies that make a specific type of equipment needed for chips, Chinese manufacturers have no real alternatives for their tools.

Whenever the restrictions go into effect, they could dry up demand from Chinese semiconductor companies for specific models of the equipment made by Applied, KLA and Lam.

“If there is trilateral agreement to restrict or block the sales of Dutch and Japanese … equipment to China, the impact could be much deeper on all tool suppliers that contribute equipment to (Chinese) production lines,” Paul Triolo, Global Technology Policy Lead at Denton’s Global Advisors, wrote in an email to the Business Journal.

The deal between the U.S., Japan and the Netherlands is still being worked out and there are few public details. Because of that, it’s difficult for experts to estimate how much the restrictions might cost Applied, KLA and Lam. But the equipment makers sometimes charge tens of millions of dollars for a single chipmaking system, depending on its complexity and the technology inside. So, missing even a small number of sales would be meaningful. Indeed, the companies each could easily see at least millions of dollars in lost sales, according to two people familiar with the industry.

Representatives of KLA, Applied Materials and Lam Research declined to comment.

Regardless of how badly the companies are hurt by the new rules, the prospect is a reminder that what happens in Washington, D.C., and in international diplomacy can affect Silicon Valley. Not that the semiconductor equipment makers needed one; they had already been reminded just a few months earlier.

In October, the Commerce Department unveiled wide-ranging restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductor equipment by U.S. companies to China, rules that were directly targeted at Applied, KLA and Lam. The three companies have estimated that those restrictions alone could cost them a combined $5.9 billion in lost sales this year. Just by itself, Applied, under CEO Gary Dickerson, has estimated the October prohibitions will reduce its 2023 revenue by as much as $2.5 billion.

Those older restrictions and the new ones come on top of other problems for the industry.

Beginning last summer, demand for memory and chips that power PCs and other consumer devices declined sharply. The swift market change has prompted big memory makers such as Intel and Micron Technology Inc. to pull back on their factory expansion plans. Those moves in turn are weighing on the equipment makers.

“Our view (is) that the semiconductor capital equipment industry is entering a severe correction,” Toshiya Hari, an analyst who covers the chip industry for Goldman Sachs, wrote in a report in January.

Lam Research said in February that it plans to cut 400 jobs in the Bay Area. Applied Materials hasn’t laid anyone off yet but recently restructured its logistics operations near Austin, which included moving jobs in-house and involving additional contractors. KLA has not announced layoffs, but company executives have said they had concerns about the macroeconomic environment

The new restrictions target lithography

Under the new rules the Biden administration is working on with the Netherlands and Japan, the Dutch will block ASML from selling to Chinese chipmakers some of its equipment that uses a process called immersion lithography. The Japanese will do the same with Nikon and anyone else that makes the advanced equipment.

The U.S. is targeting immersion lithography equipment because it is one of the critical choke points for chip manufacturing. Semiconductor makers use lithography systems to draw circuits and other features onto circular silicon wafers. Immersion is a specific technique used in lithography to reduce the size of the components drawn on the wafers.

Without ASML or Nikon’s lithography machines, it’s impossible to print chips that are based on technology that’s years-old, let alone make the kinds of cutting-edge processors that are used for smartphones or artificial intelligence applications.

If they’re not able to buy those lithography machines, the Chinese chipmakers will likely curtail their purchases of at least some of the etching, deposition and quality control machines made by Applied, KLA and Lam. Those companies’ tools (see sidebar for an explanation of what each company makes) work hand-in-hand with the lithography systems; without the lithography equipment, Applied, KLA and Lam’s equipment is essentially superfluous.

The restrictions on lithography equipment follow those the Commerce Department put in place in October that took direct aim at Applied, KLA and Lam’s advanced etching, deposition and quality control equipment. Those October rules aimed to block Chinese chipmakers from manufacturing the most advanced chips and hobble their current capabilities. The new ones the Biden administration is developing with the Netherlands and Japan attempt to go even farther by hindering the Chinese semiconductors companies’ ability to make less advanced chips based on mature technology, experts say.

But the potential loss of equipment sales is only part of the concern for the Silicon Valley toolmakers. The machines they sell need to be regularly serviced and maintained to continue producing defect-free chips. For each of the companies, service contracts have become an important and growing source of revenue. If the new restrictions on lithography tools hamper sales of the local equipment makers’ etching and other machines, those lost tool sales could lead to lost service revenue.

Exactly how much the in-the-works restrictions could hurt Applied, KLA, Lam Research is anyone’s guess. Neither the White House nor the Commerce Department, which handles export controls, has offered any specifics about the U.S.-Japan-Netherlands deal. A representative for the National Security Council, the White House agency that is handling portions of the negotiations with the Dutch and the Japanese over the new export controls, declined to comment.

Likely, the cost to the companies of the new rules won’t be anywhere near the $5.9 billion they estimated as the cost of the October regulations. That’s because those earlier regulations already barred the local equipment makers from selling their most advanced — or “leading-node” — chipmaking equipment to China, said Bernstein chip analyst Mark Li. That also tends to be their priciest products.

“Since the leading-node equipment from the U.S. has been banned already, the incremental damage to Applied, KLA, Lam Research … should be small,” Li said.

The equipment companies will likely eventually know some of what’s in the trilateral agreement. Other details may trickle out through a Japanese regulatory process. But the public at large may never know the exact provisions.

For their part, the Dutch in particular don’t want to make public the specifics because trade restrictions they’ve made outside the auspices of the European Union could cause “consternation” there, said William Reinsch, a former undersecretary of commerce for export administration.

“I’m sure the United States would like to wave (the deal) around and publicize it, but I don’t think that they will, and I don’t think the other two countries have an interest in publicizing it,” Reinsch said.

© 2024 American City Business Journals. All rights reserved. Use of and/or registration on any portion of this site constitutes acceptance of our User Agreement (updated April 19, 2024) and Privacy Policy (updated December 19, 2023). The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of American City Business Journals.